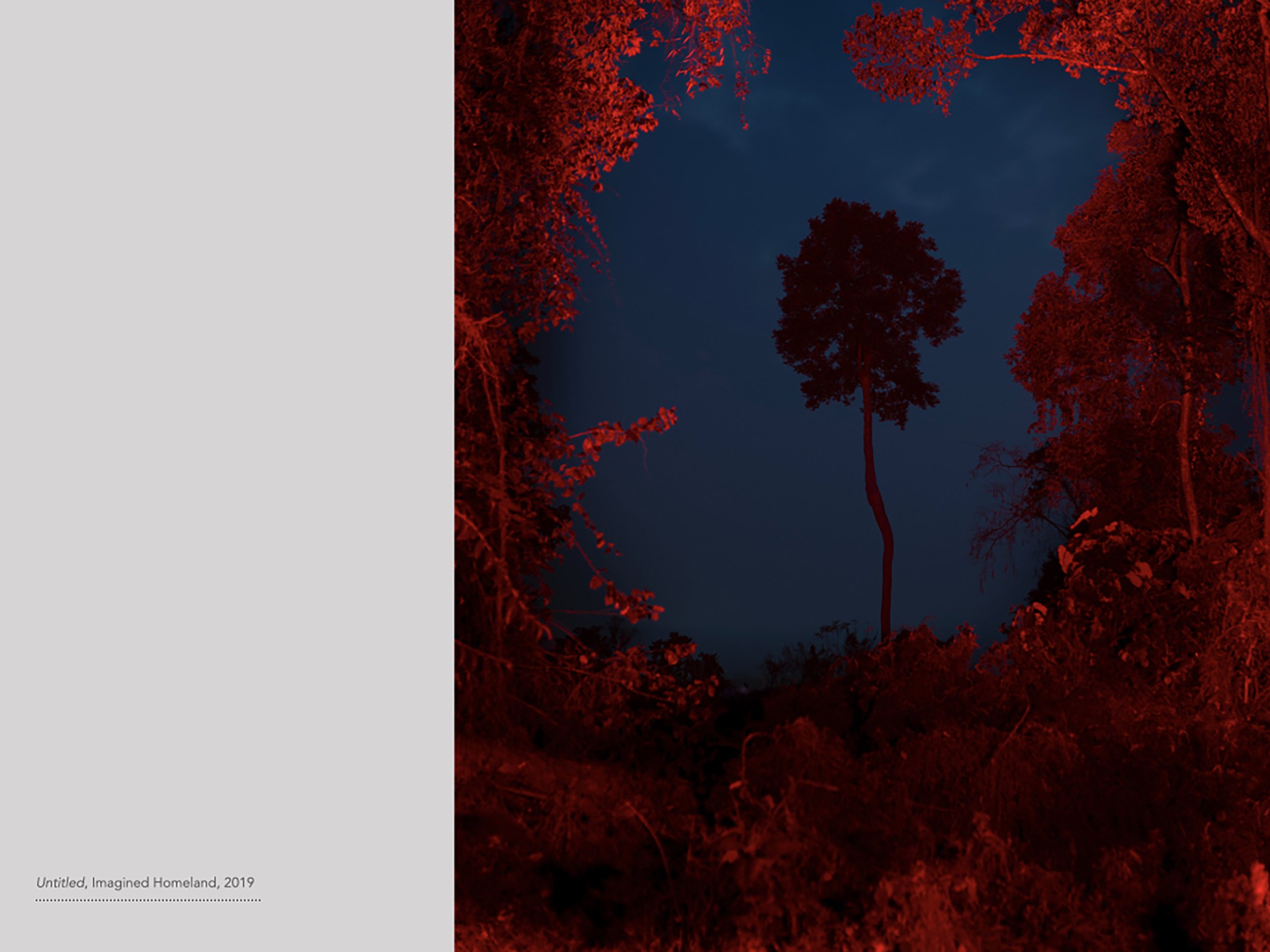

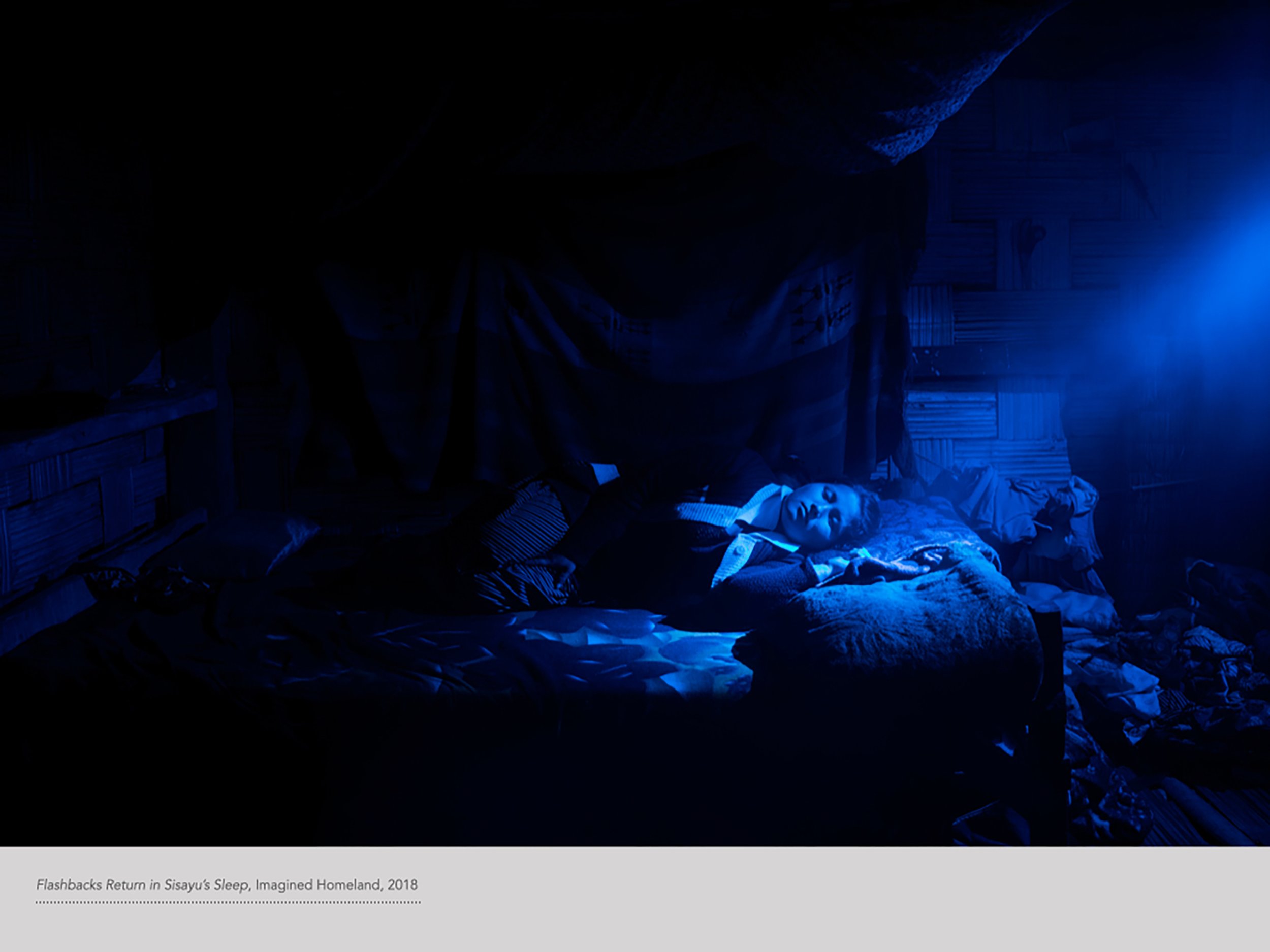

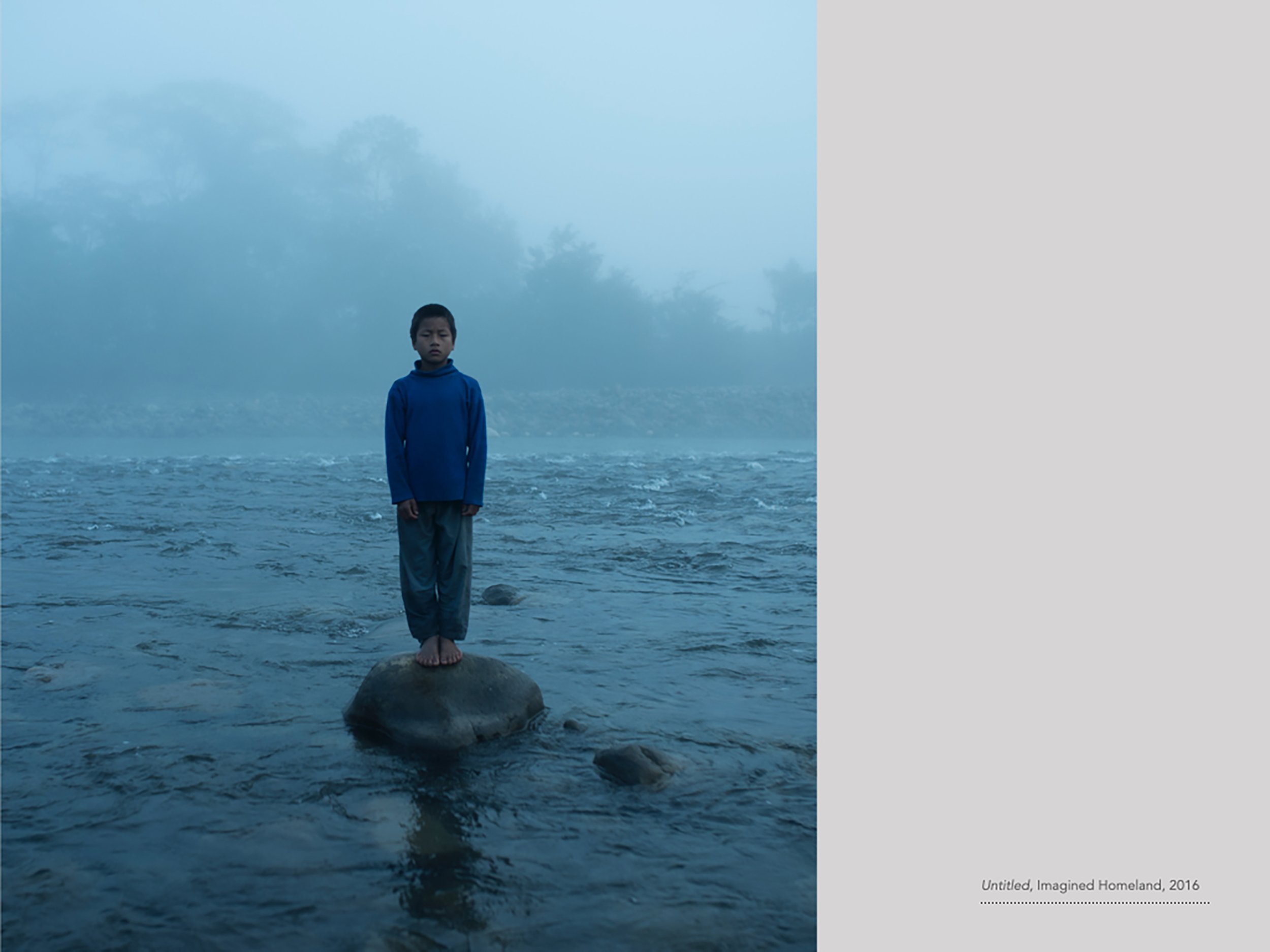

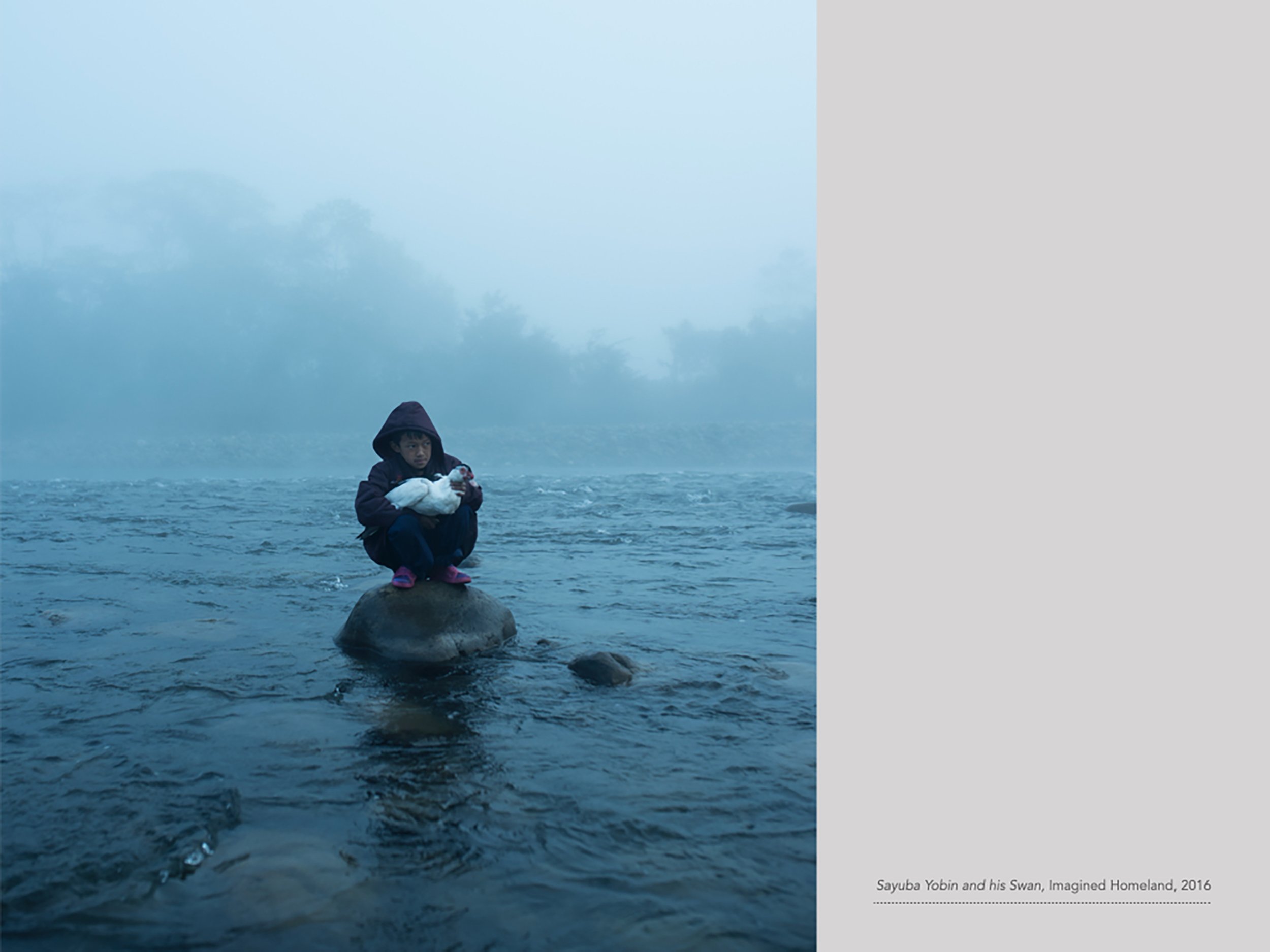

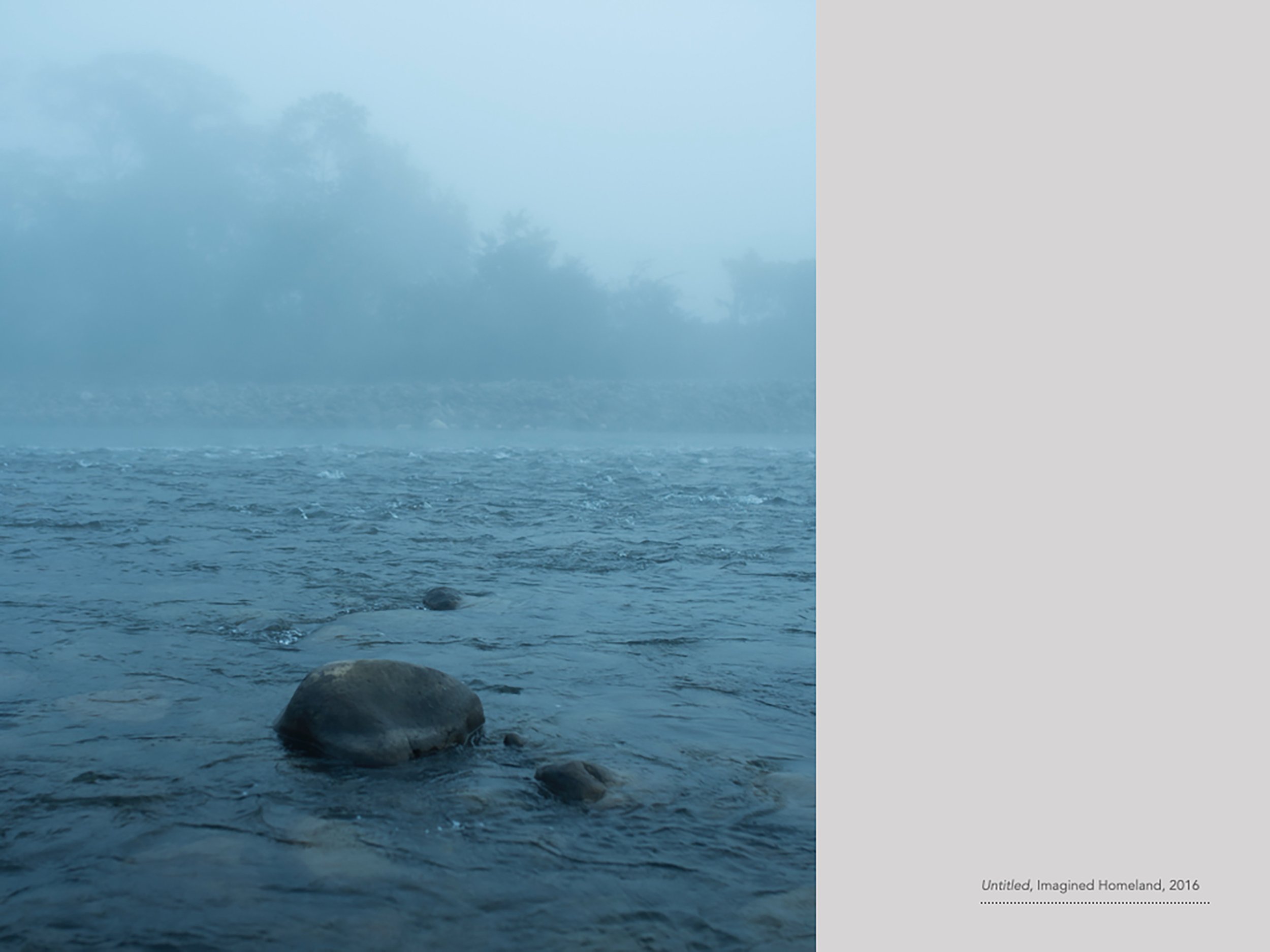

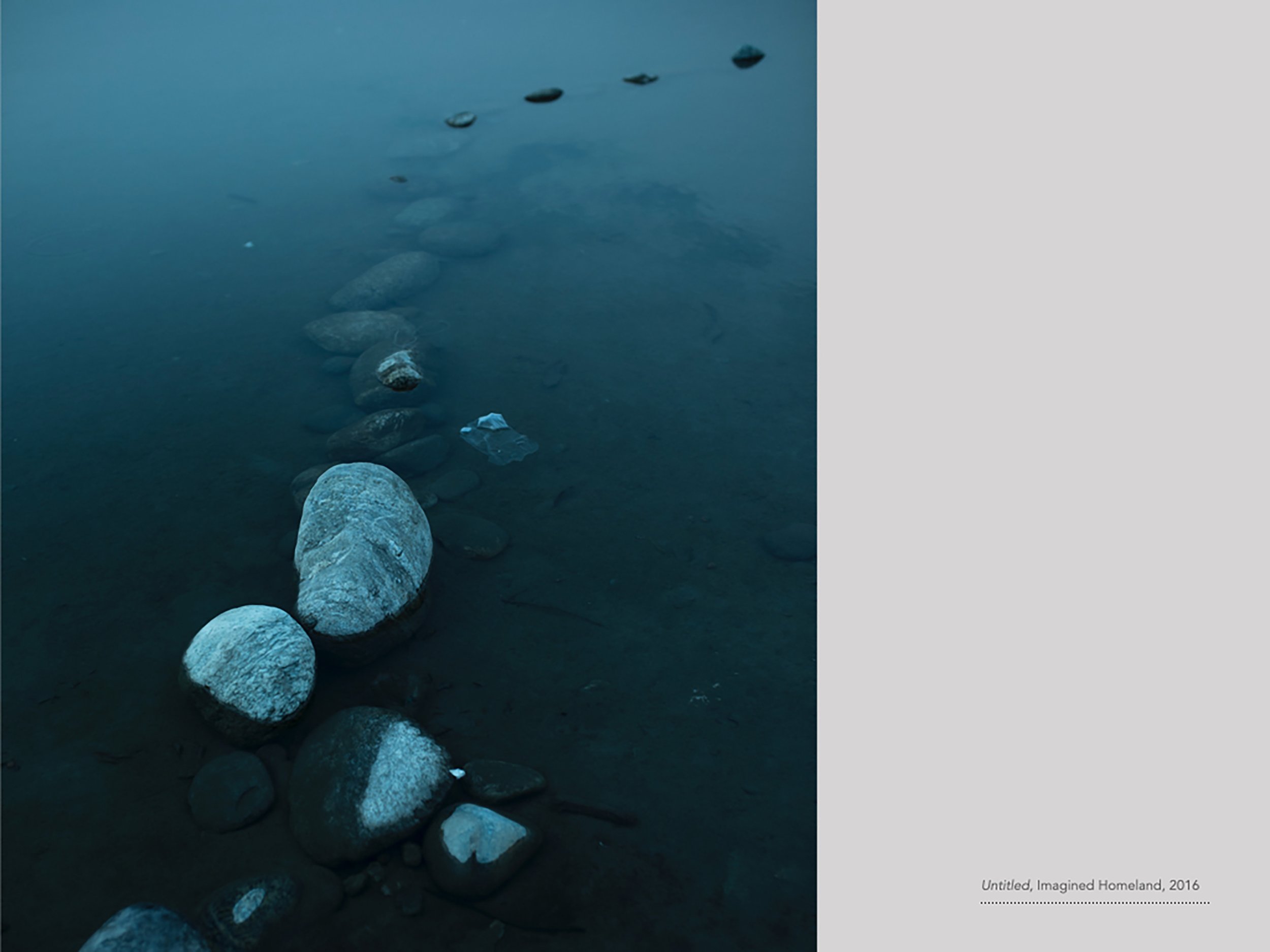

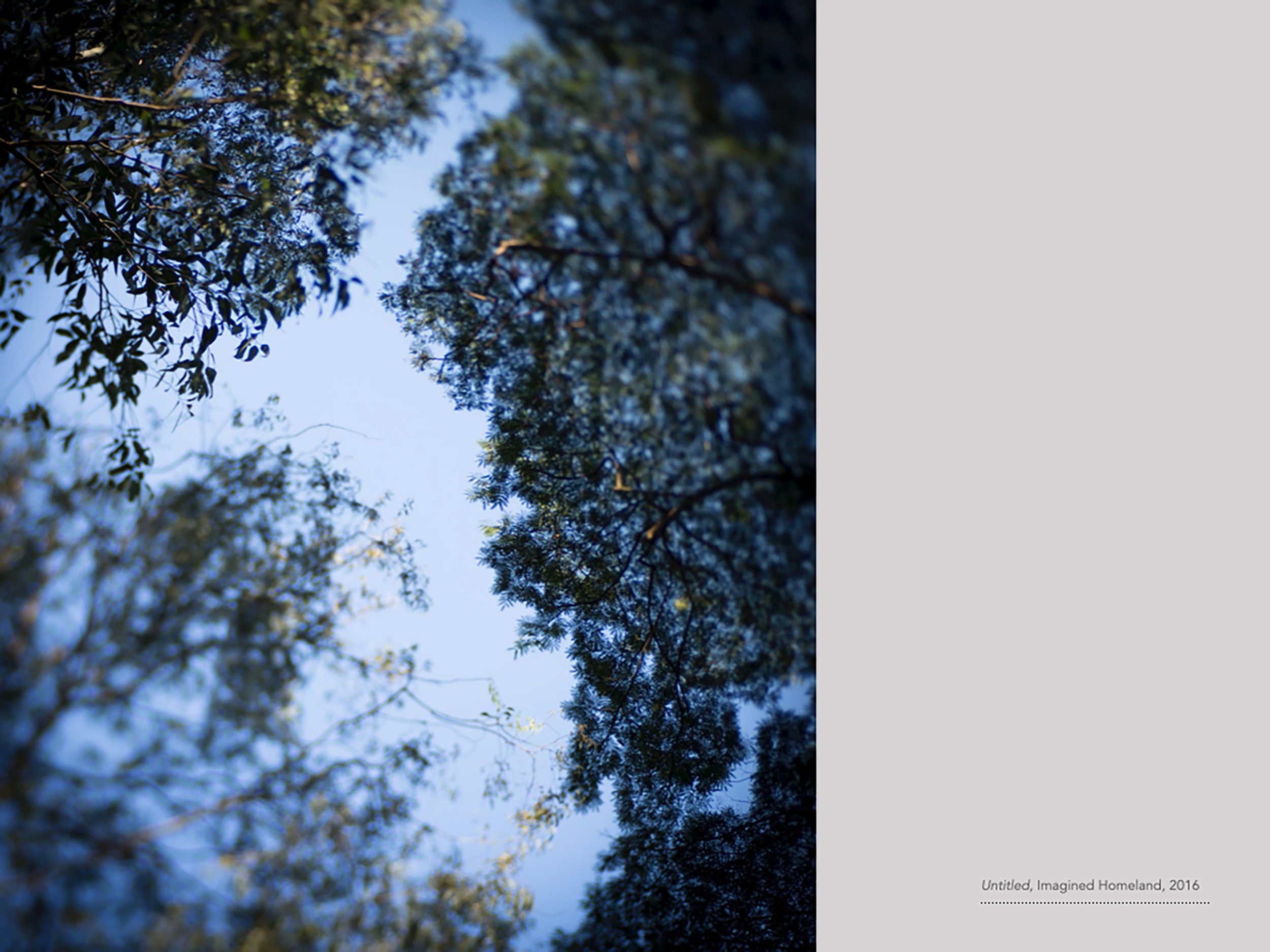

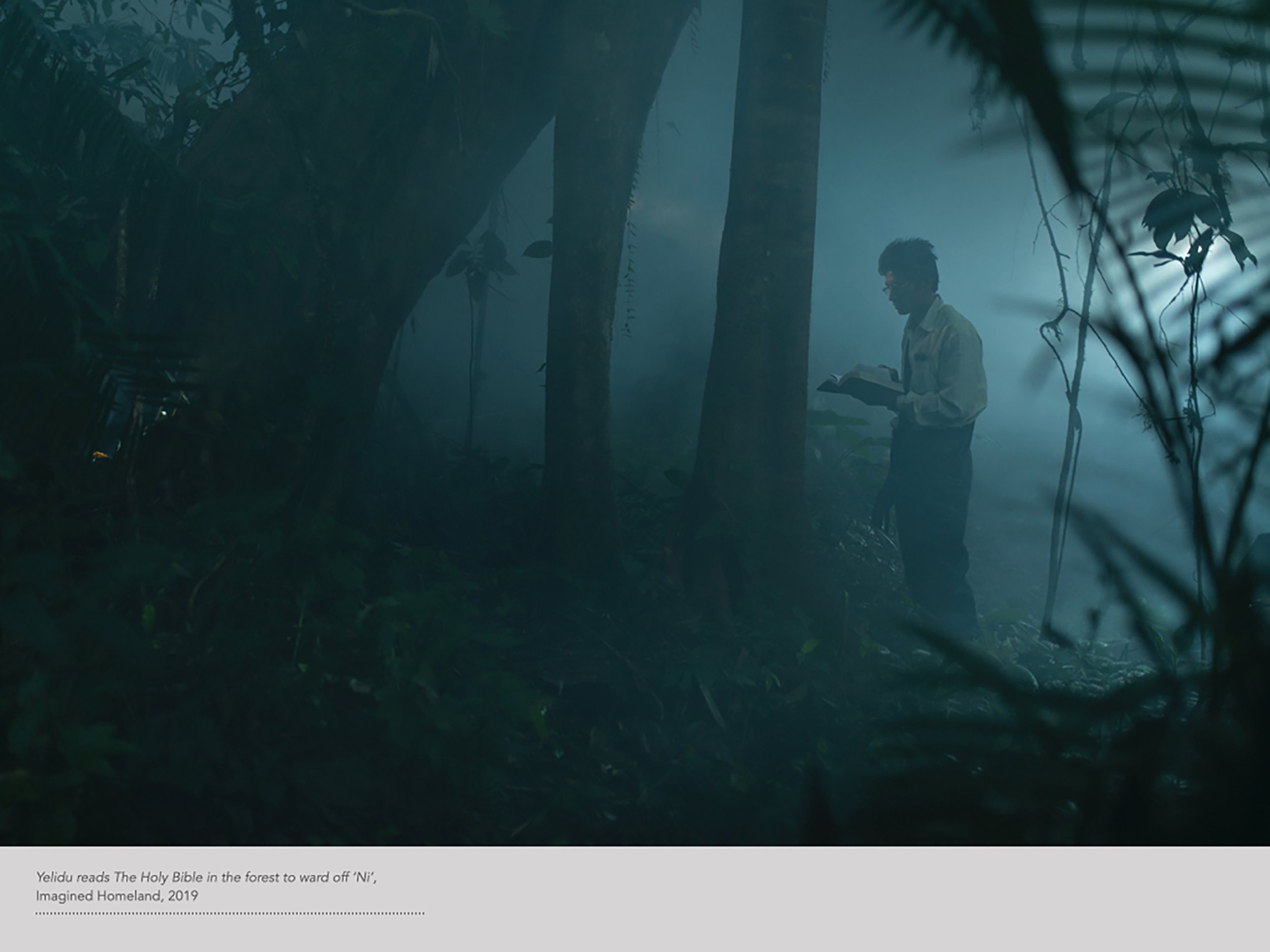

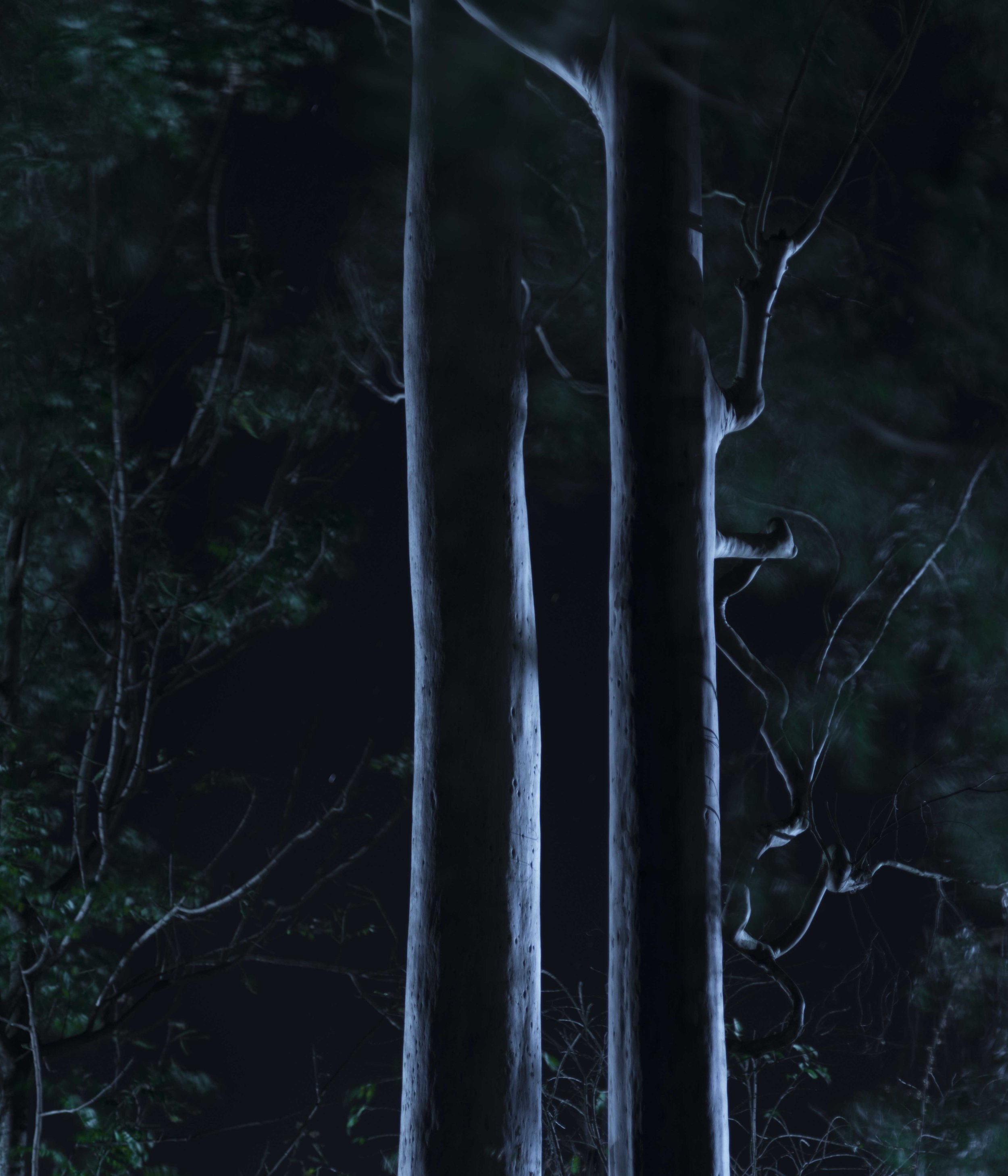

““Rejecting colonial documentary methods, De tells the story of Arunachal Pradesh’s Lisu people by harnessing mythological symbolism in his cinematic stills”.

”

Magical Photos from an Isolated Community in the Forests of India

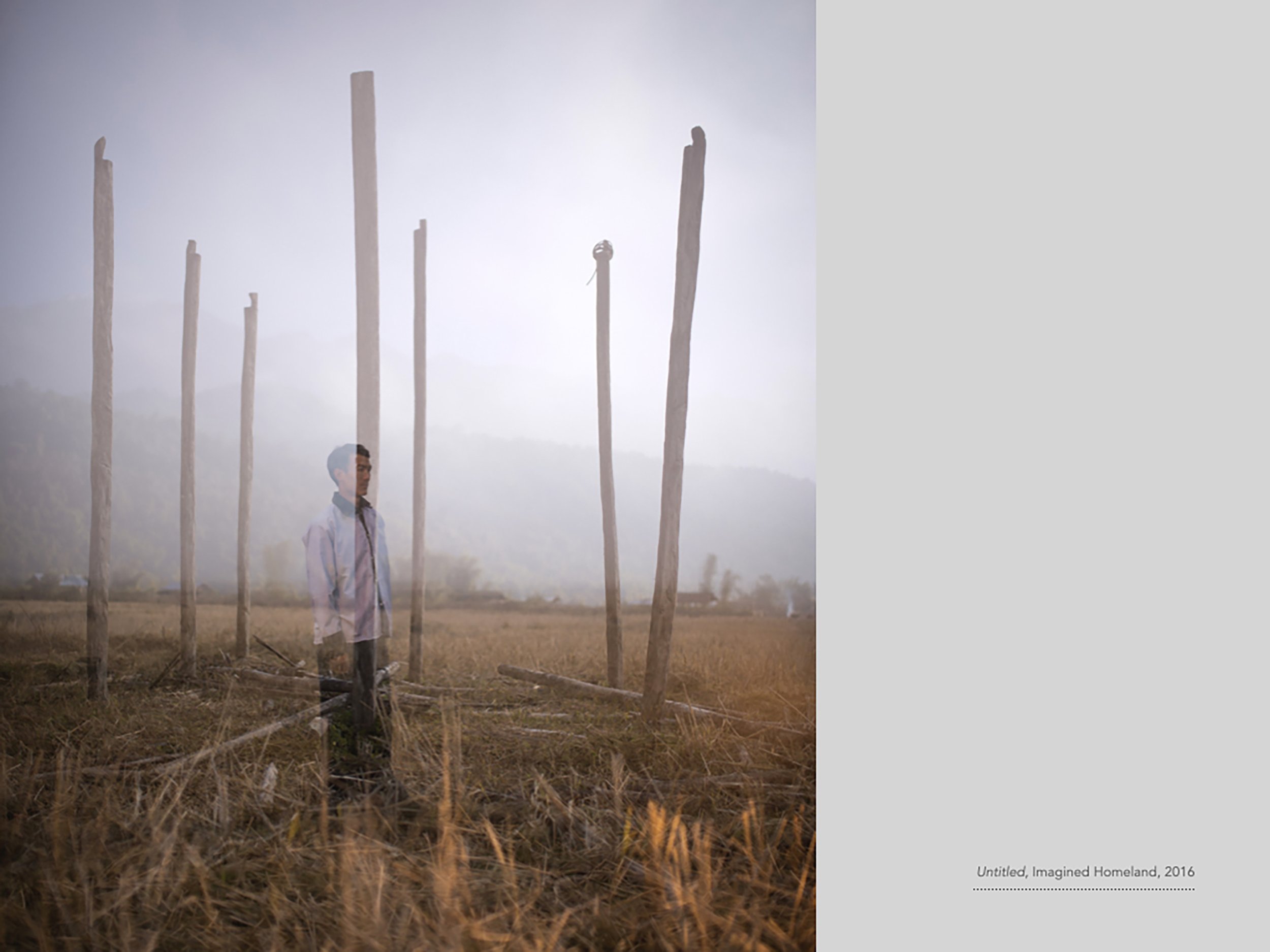

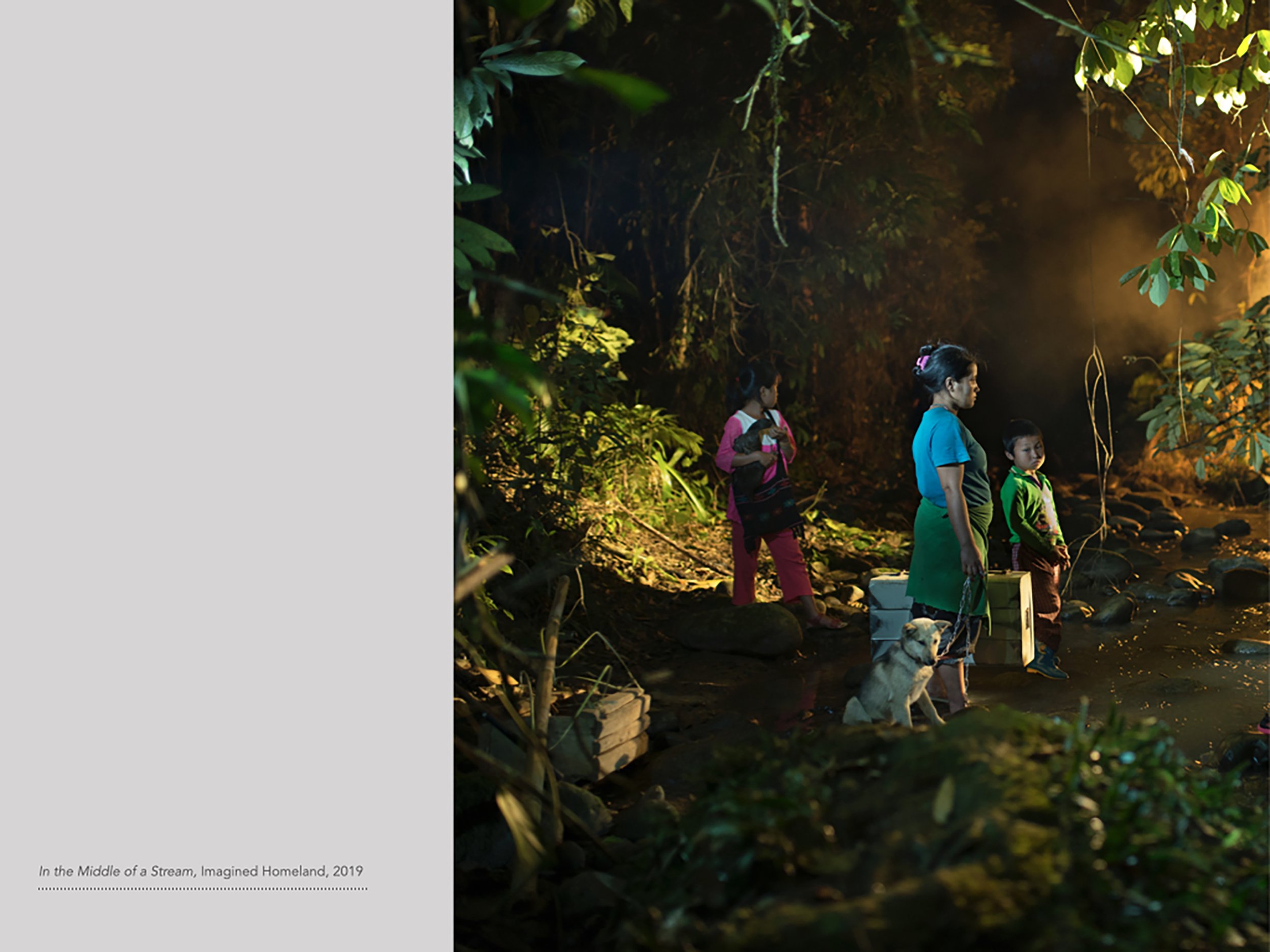

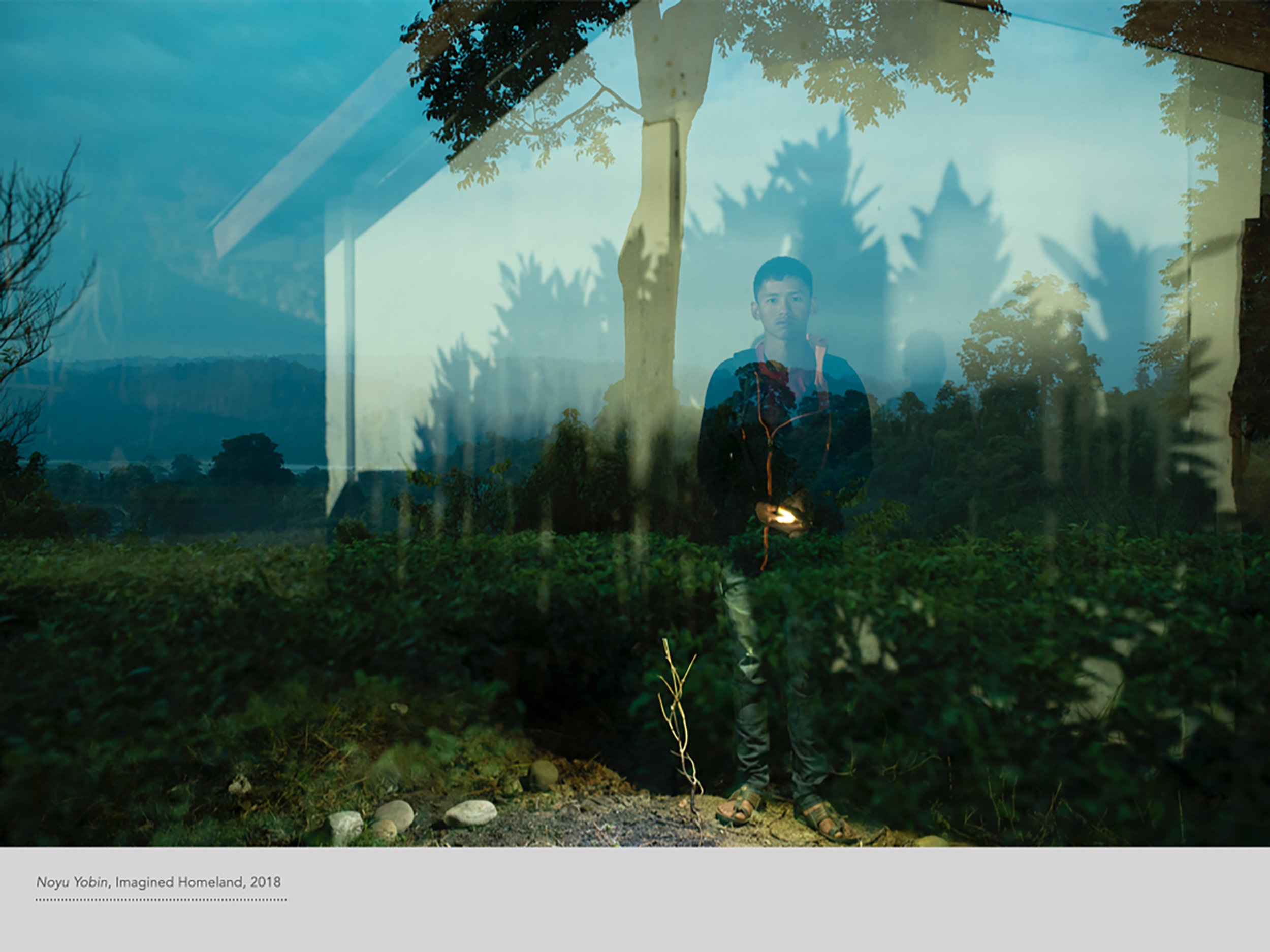

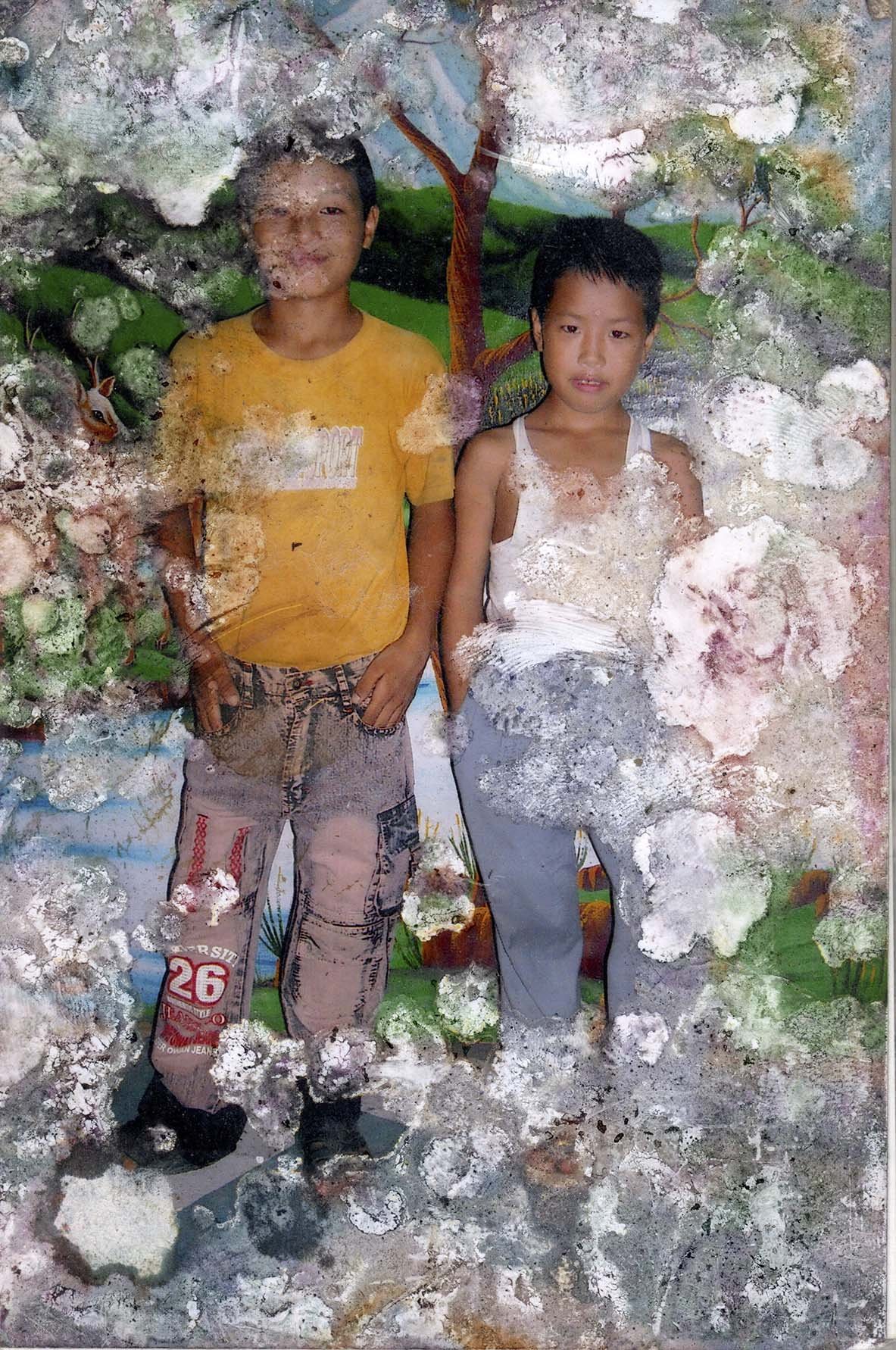

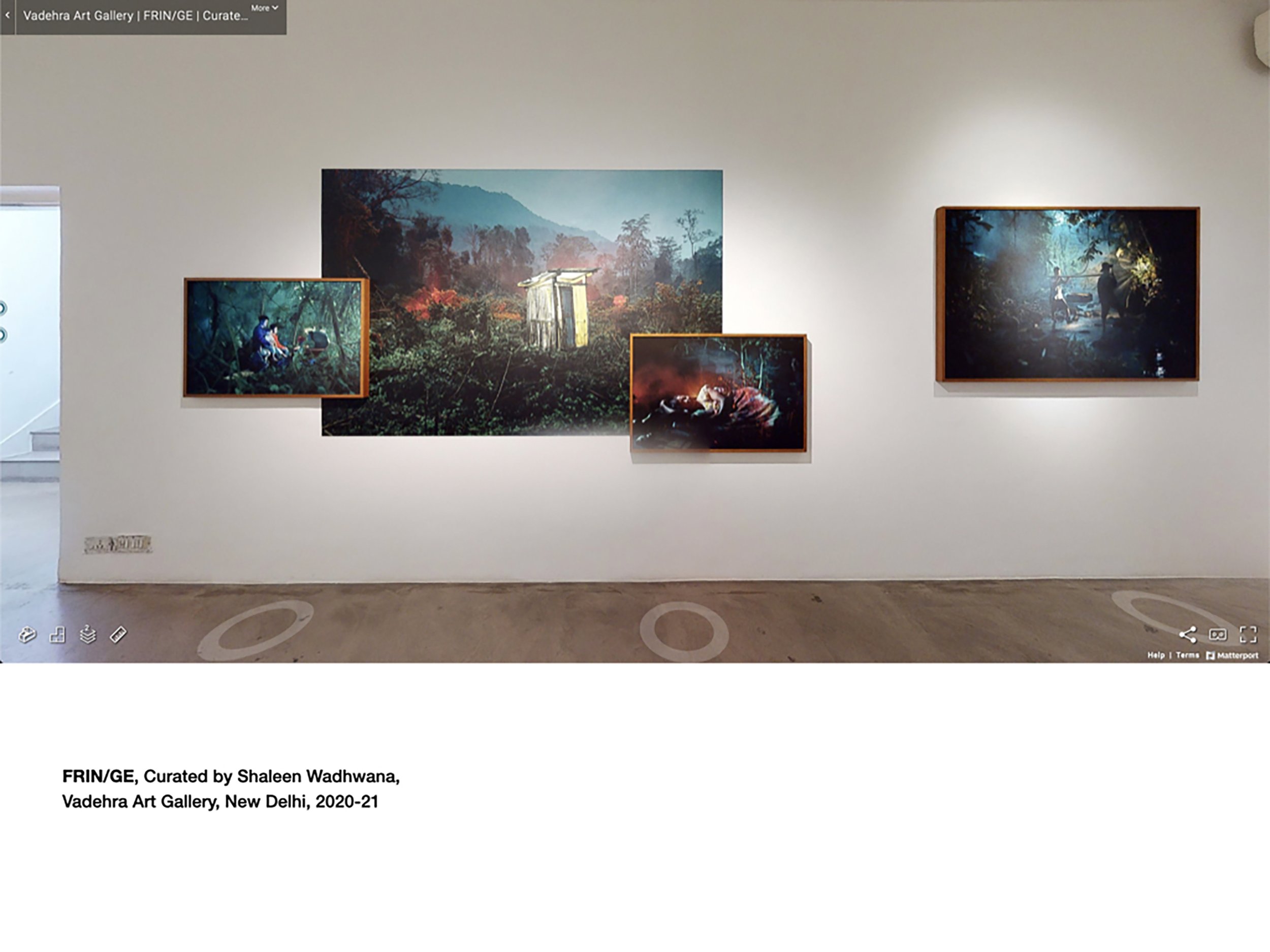

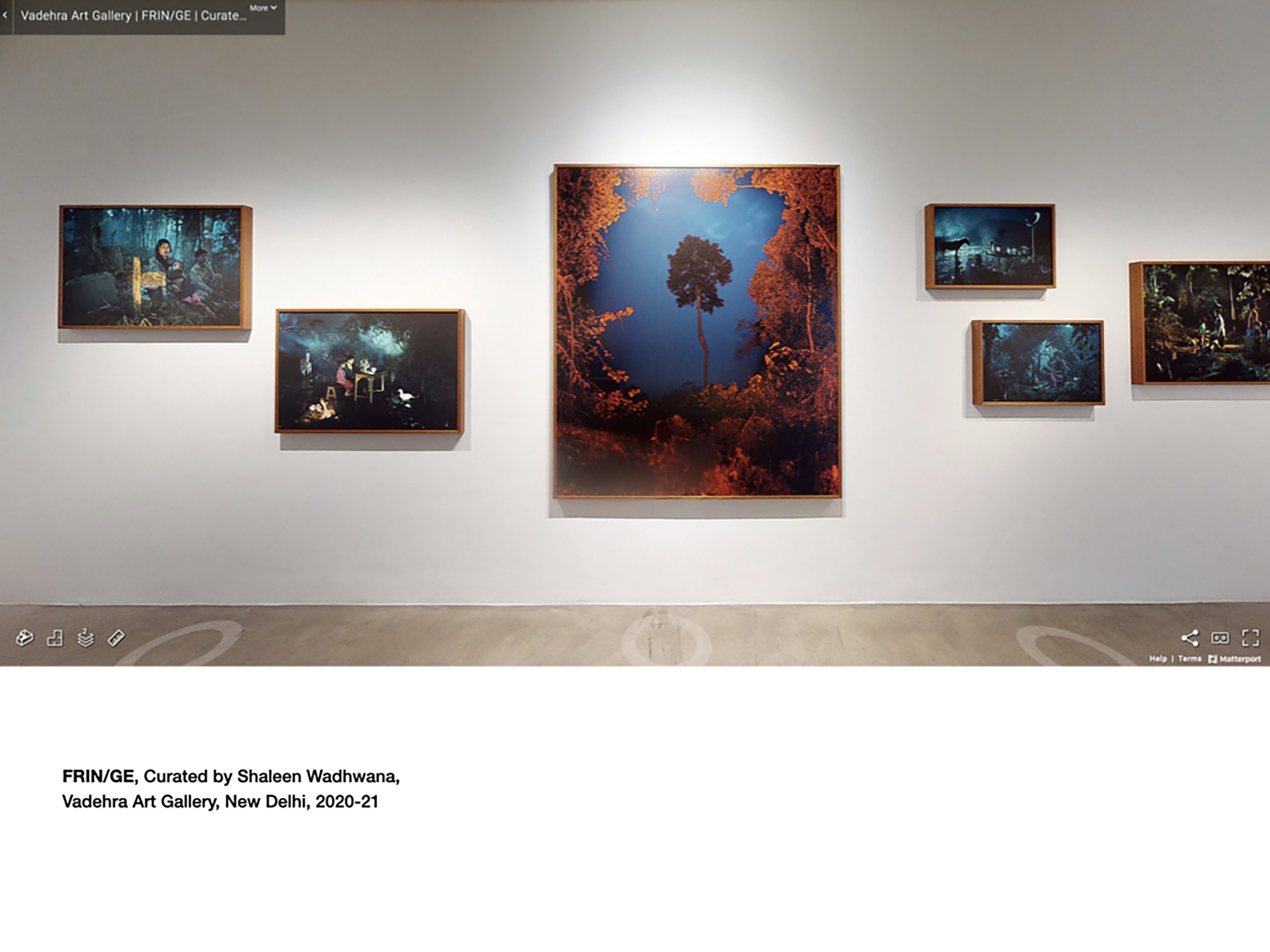

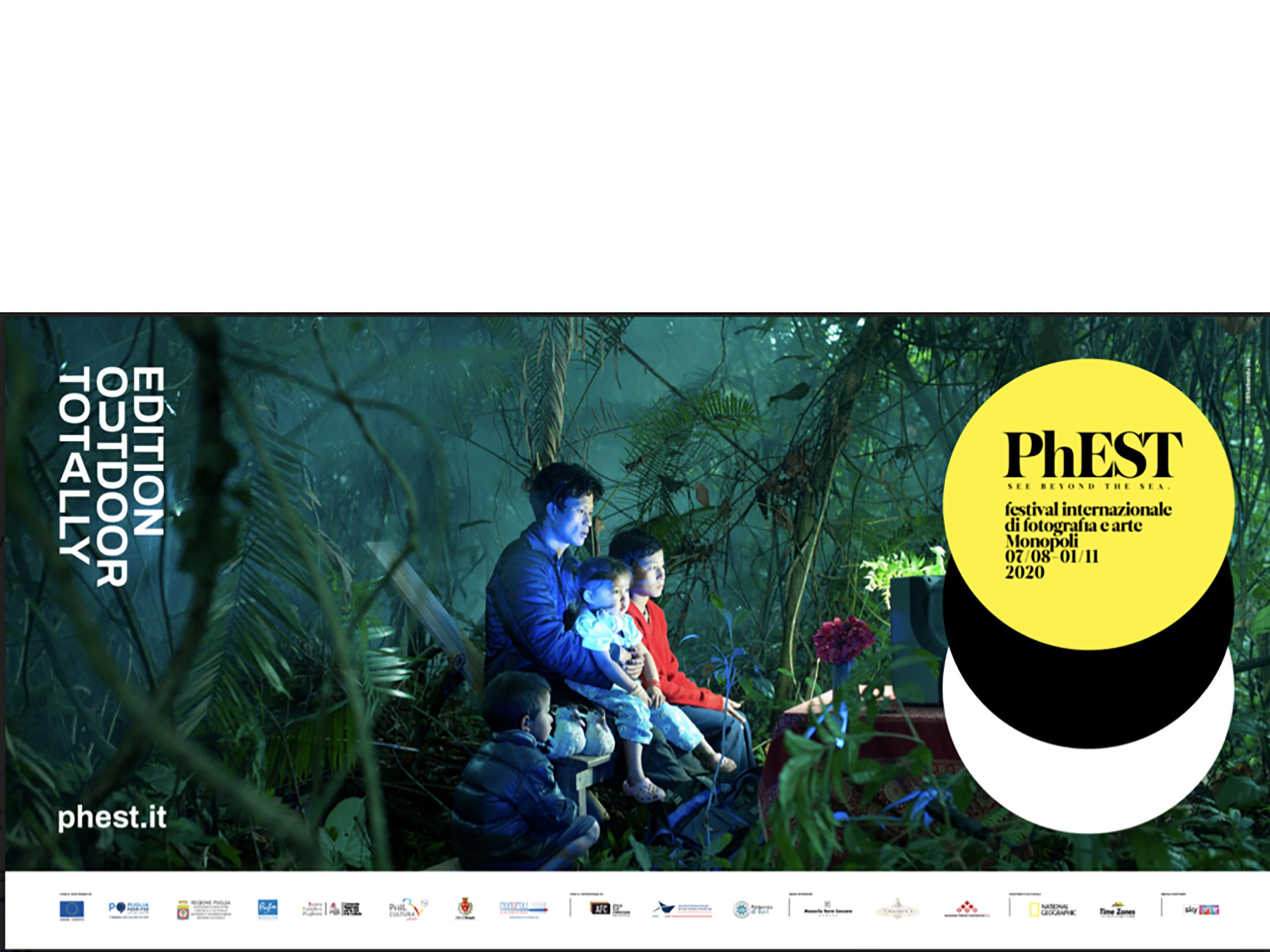

““De has taken an unconventional approach to telling the story of the Lisus; since the birth of photography, oppressed communities have been cast as “exotic” or “primitive” by those standing behind the camera. Instead of taking a “colonial-anthropological” look at these families and individuals, he’s chosen something closer to magical realism. The photographs themselves are rich with symbolism, and the Lisus’ animals and their environment become key characters in the narrative.””

Images:

Artist Statement:

Alienation of man from nature has been calamitous. Cartesian dualism arrogates all intelligence and agency to the humans with none to the nonhuman living beings (Amitav Ghosh, 2016) rendering the latter as—passive unintelligent liabilities—meant to serve the human race, thereby ‘othering’ them. Following the Enlightenment theory propagated in the 17th & 18th century, we have projected man as exceptional, and thus distinctly separate from the rest of the earth’s ecosystem, of which the human is just another cog in the wheel. We have glorified our exploits exemplifying ourselves as exceptional. But would the tigers and deers, the octopus and phytoplanktons, the forests and the mountains and the butterflies and moths, to name a few, concur with this history as the ‘absolute history’? If they could record the historical (and the present), what would their archives reveal?

Posthumanities scholar Eduardo Kohn in How Forests Think (University of California Press, 2013) writes, “How other kinds of beings see us matters. That other kinds of beings see us changes things.” Indigenous communities living closer to nature have always been aware of this circuitous relationship between the distinctly human, nonhuman living beings and other elements of nature.

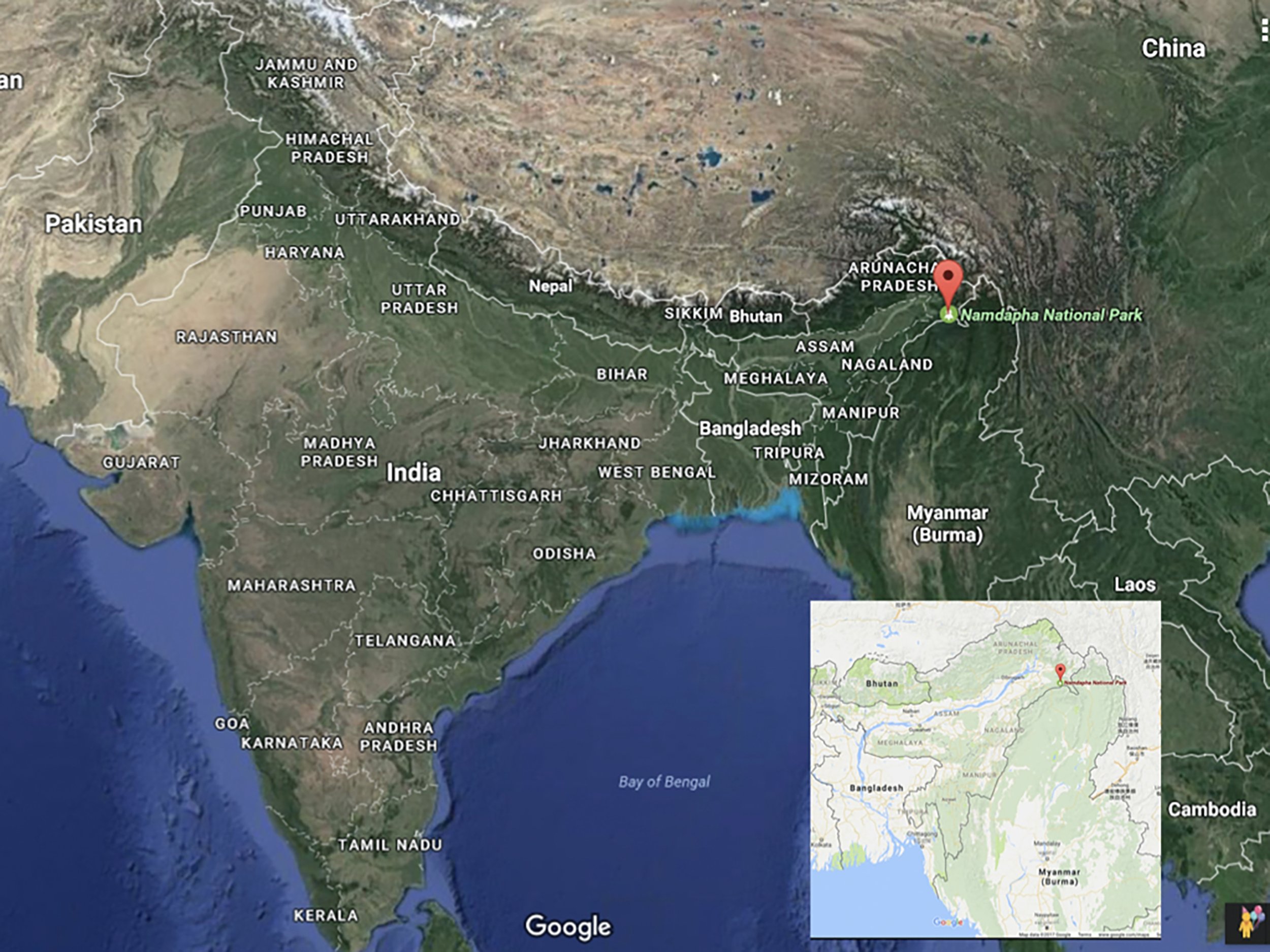

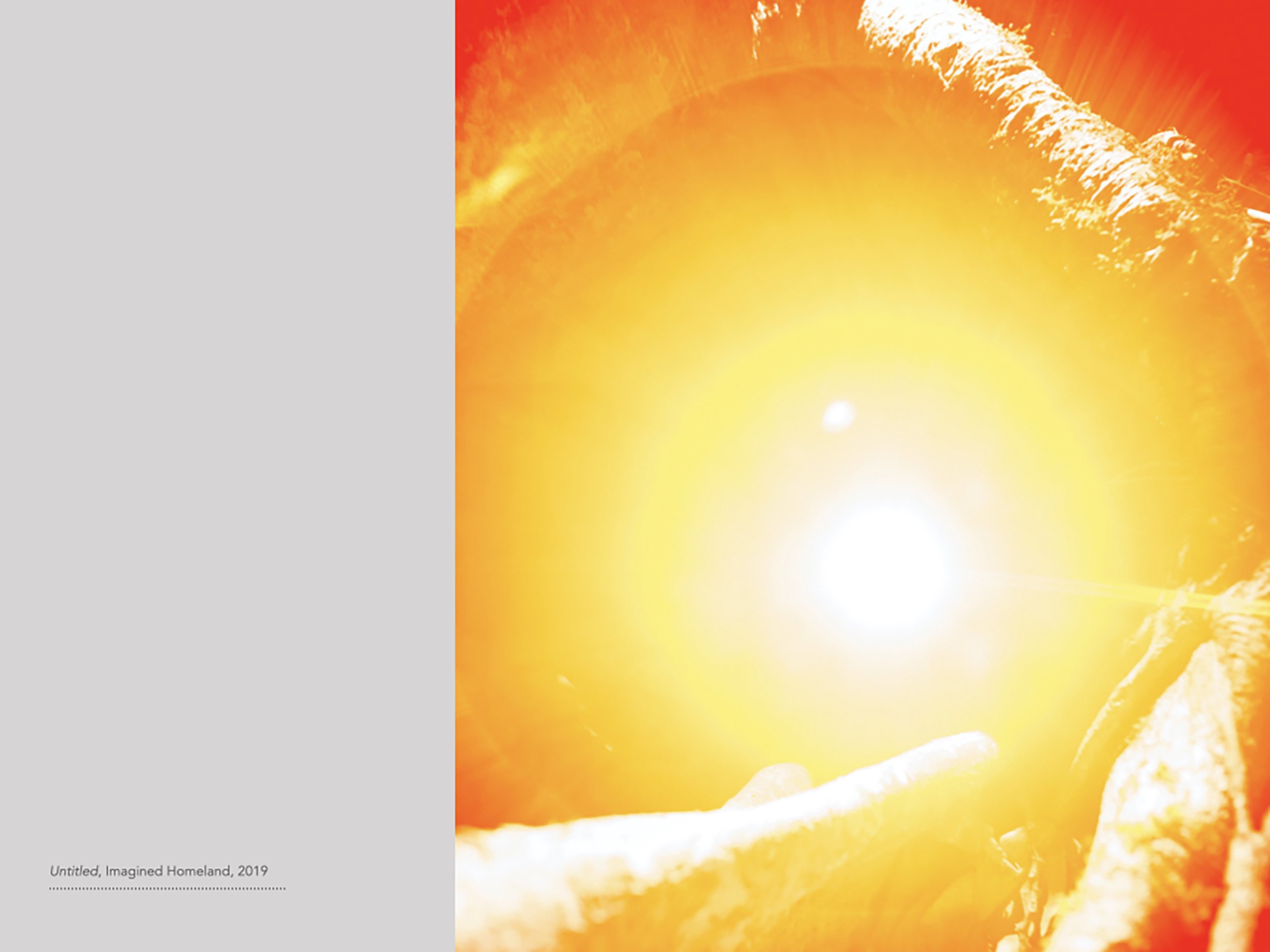

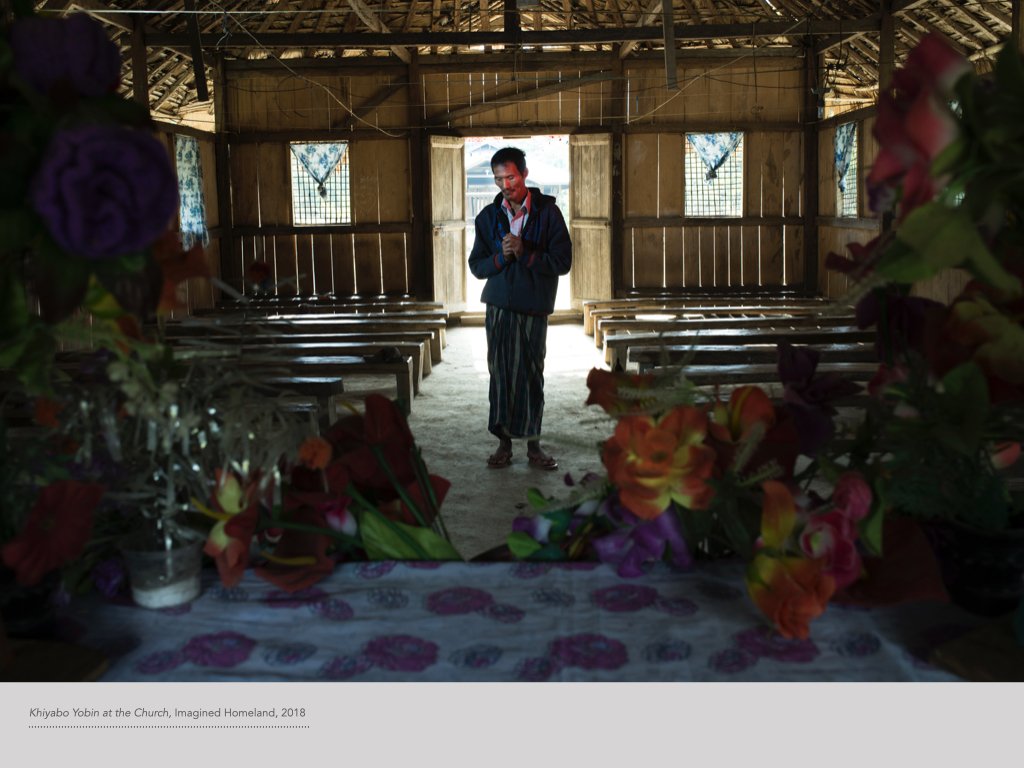

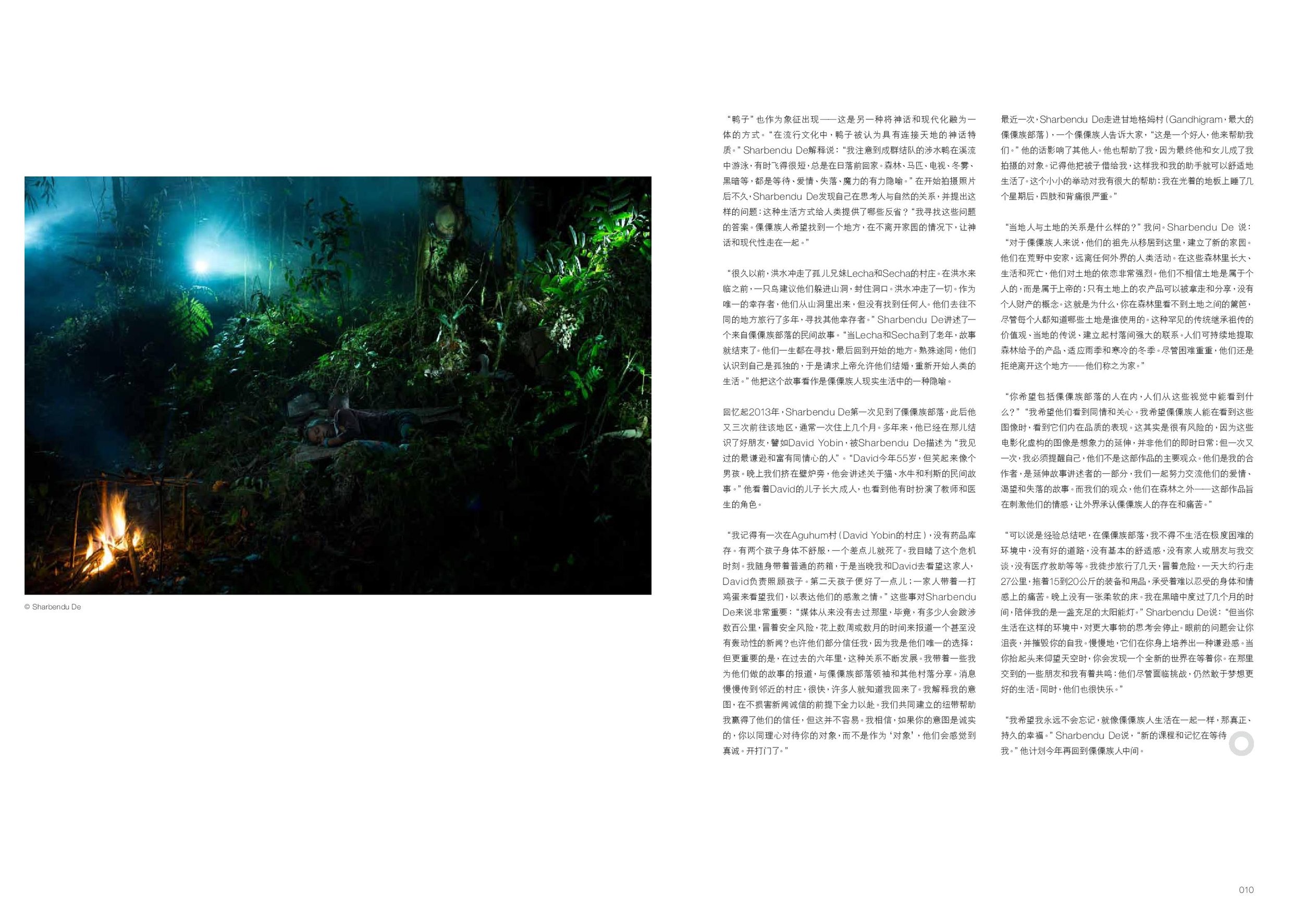

The lesser known Tibeto-Burman indigenous Lisu community living inside the jungles of Namdapha National Park & Tiger Reserve (NNP) in India’s remotest northeastern state Arunachal Pradesh, believe that ‘a parallel invisible world coexists in the same time-space continuum’. They call it Maamimu and the invisible humans living there as Musi. They say that for each Lisu, there is a similar looking Musi in Maamimu, and should one suffer or die, the same fate meets the other, alluding to the ‘bush soul’ concept. Invisible portals connect both worlds and stories of interactions with the Musi exist in the Lisu world. Their relationship with the forest and its innumerable elements are influenced by similar belief systems making them more respectful of nature and its cohabitants. Cohabiting symbiotically with nature as a self-sufficient community and as 'mythical entities’ (A. K. Ramanujan) the Lisus are harbingers of hope. Their gentle stewardship of life amidst the darkness of the forest is illuminating.

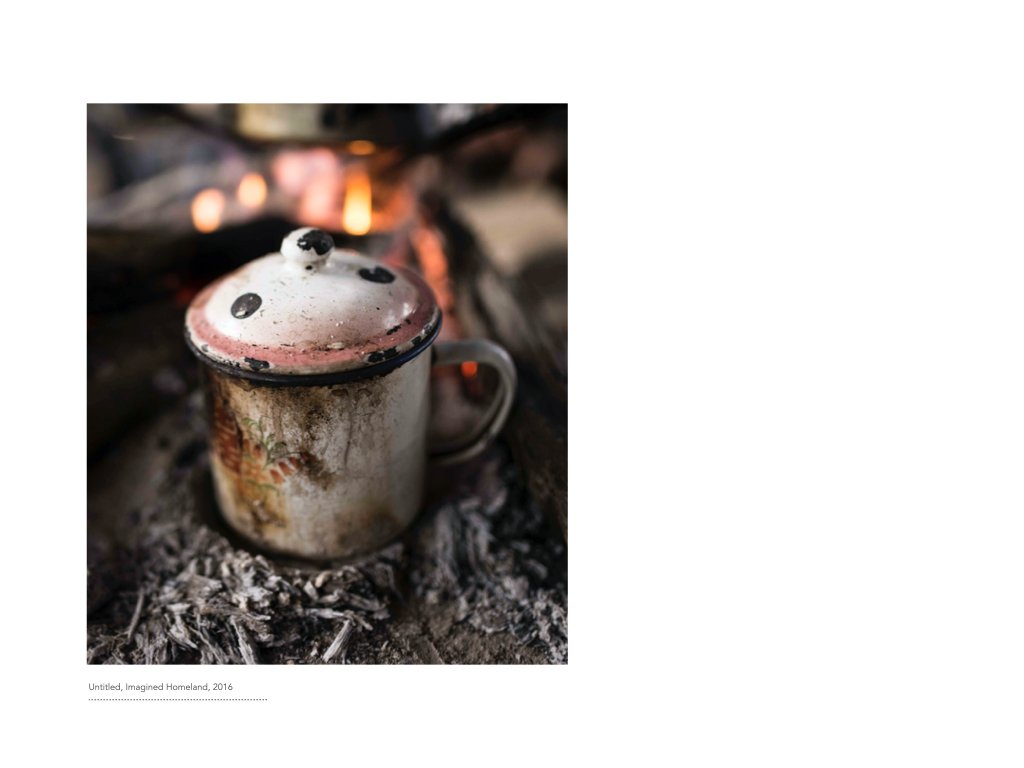

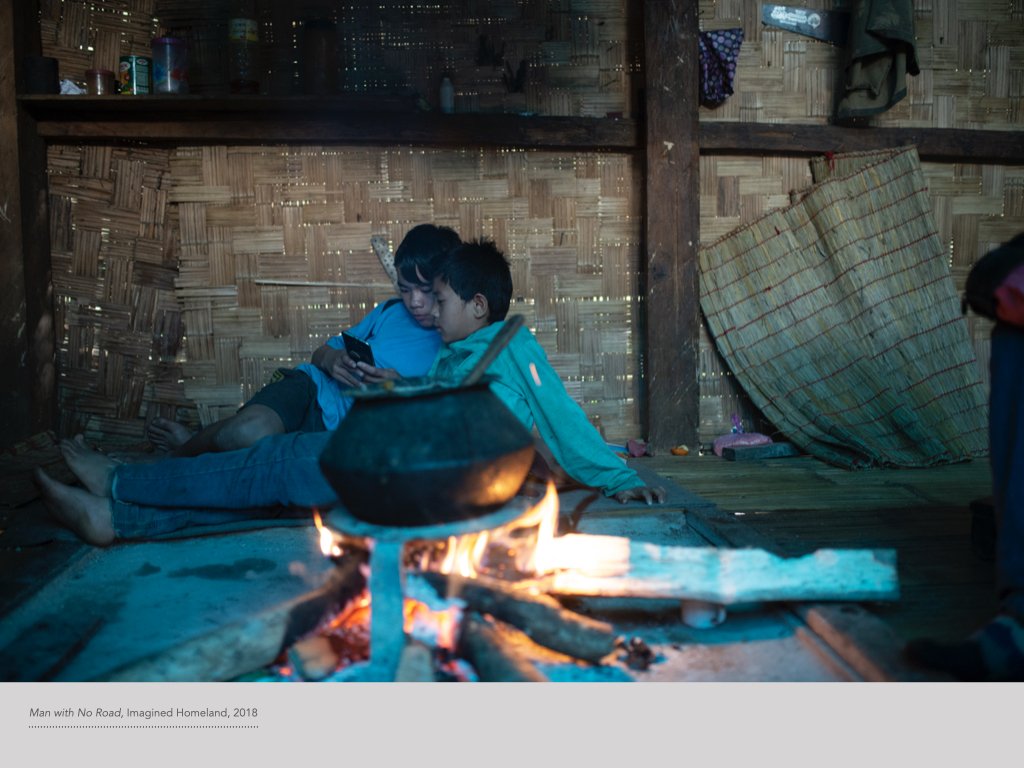

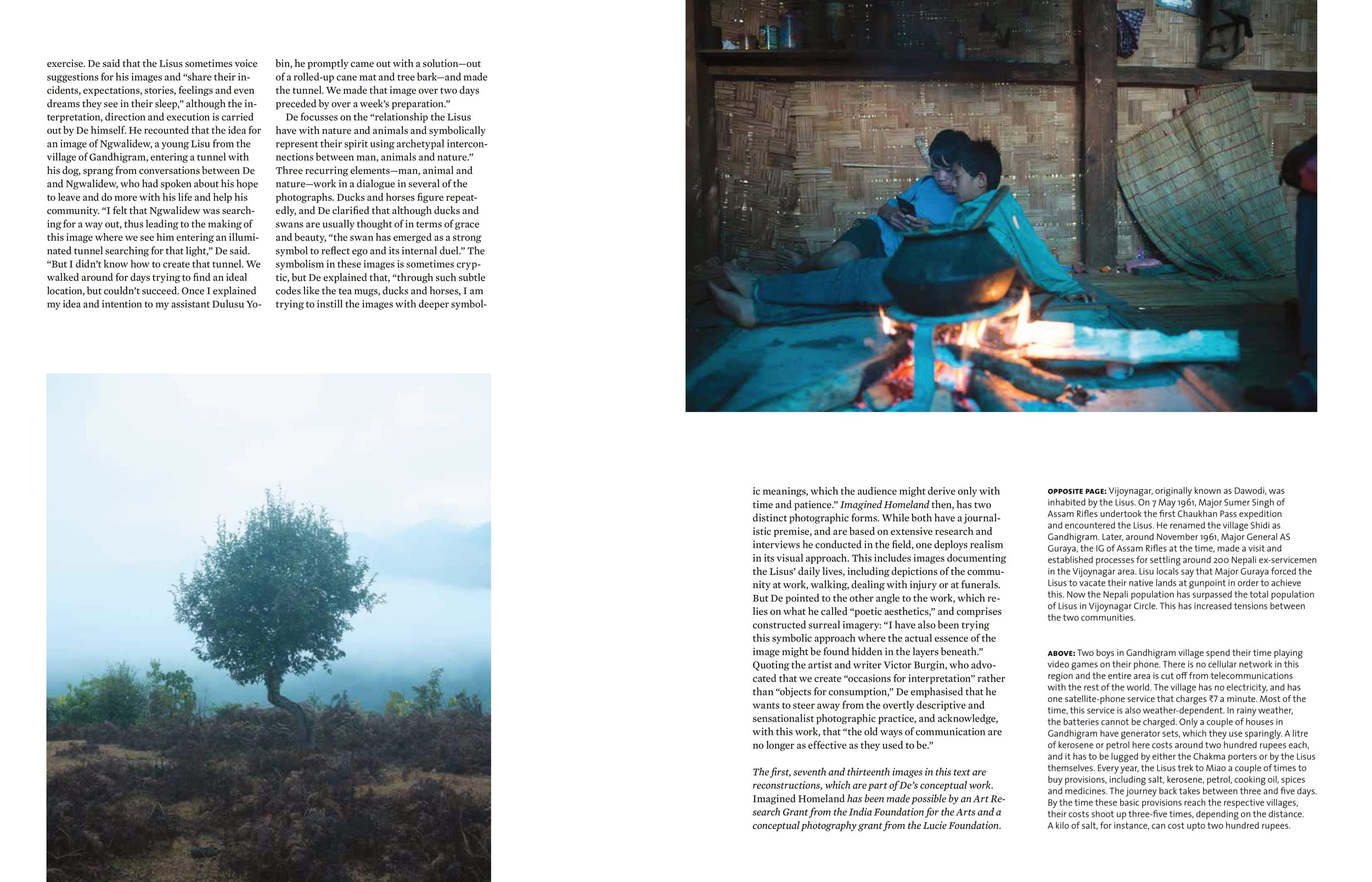

Made over seven long years (2013-19), I rooted my practice in ethnographic research, extensive field work, journalistic interviews. I also borrowed from dream symbolism and adopted magic realism and poetic aesthetics to allude towards the feelings the Lisus feel, and their relationship with nature—the intangible cultural assets that define and distinguish them from the urban monetised societies. Whilst the series represents an unrepresented indigenous community, it also counters the colonial-paternalistic gaze opening up new portals of imaginations.

About the Lisus:

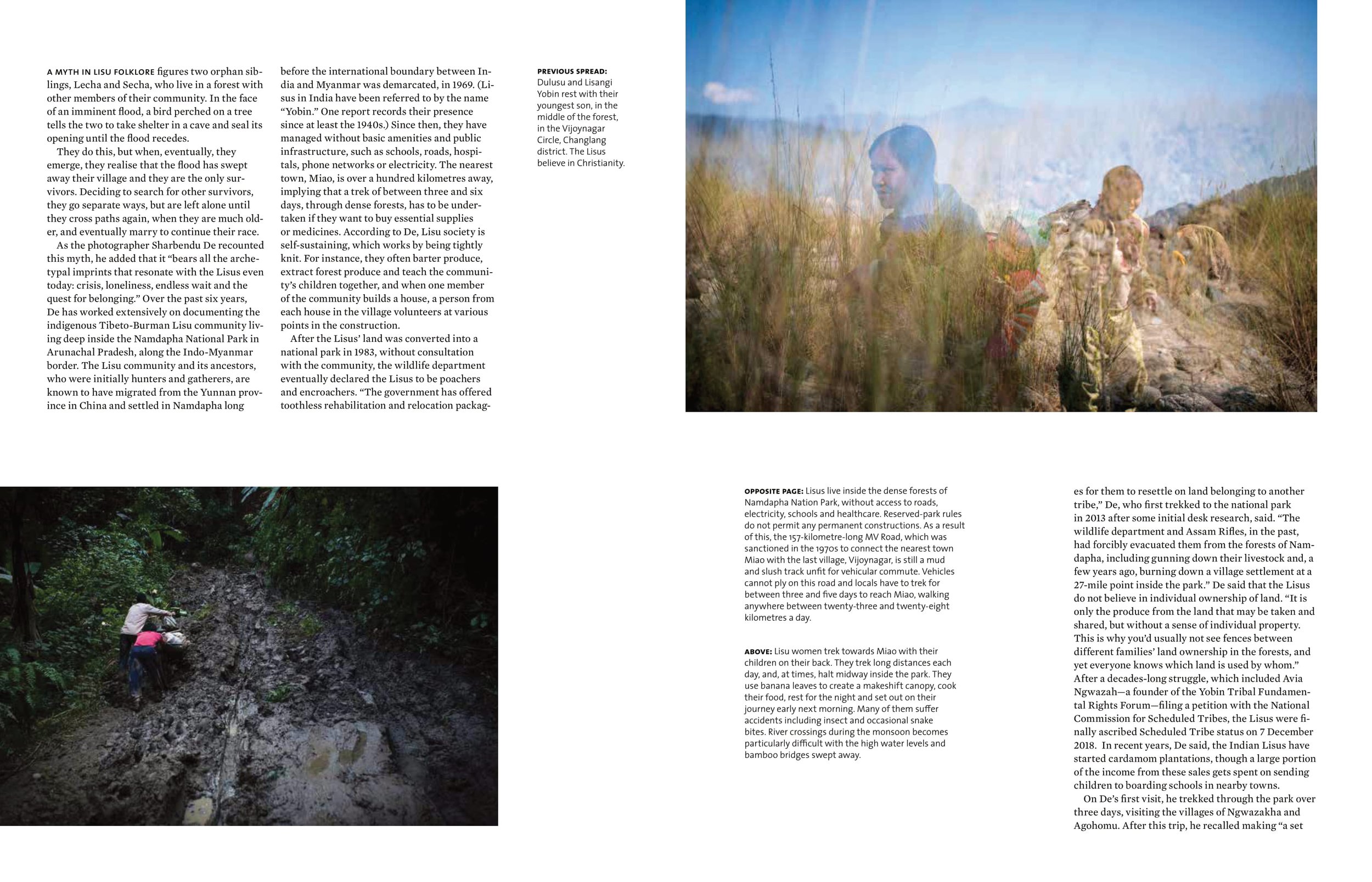

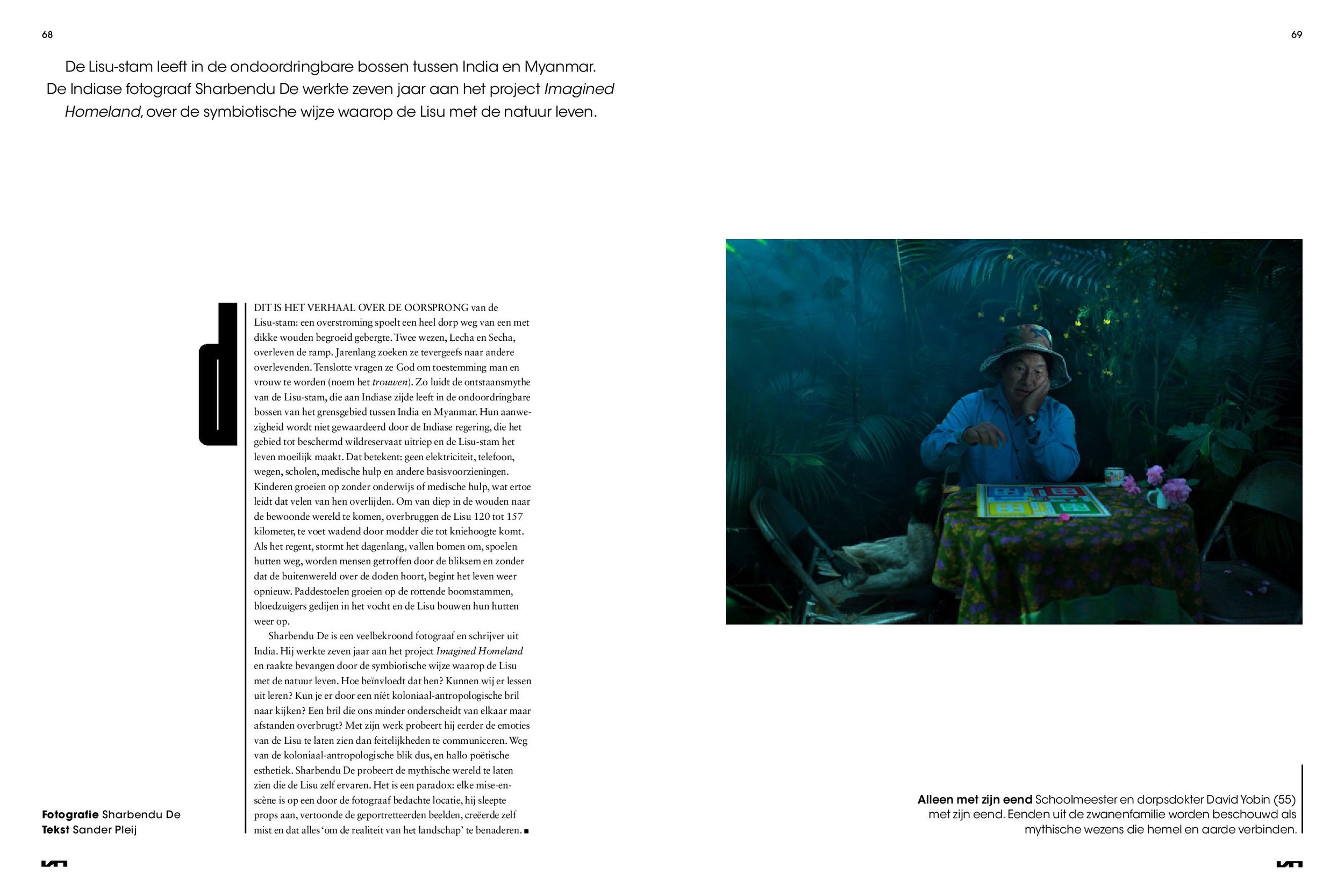

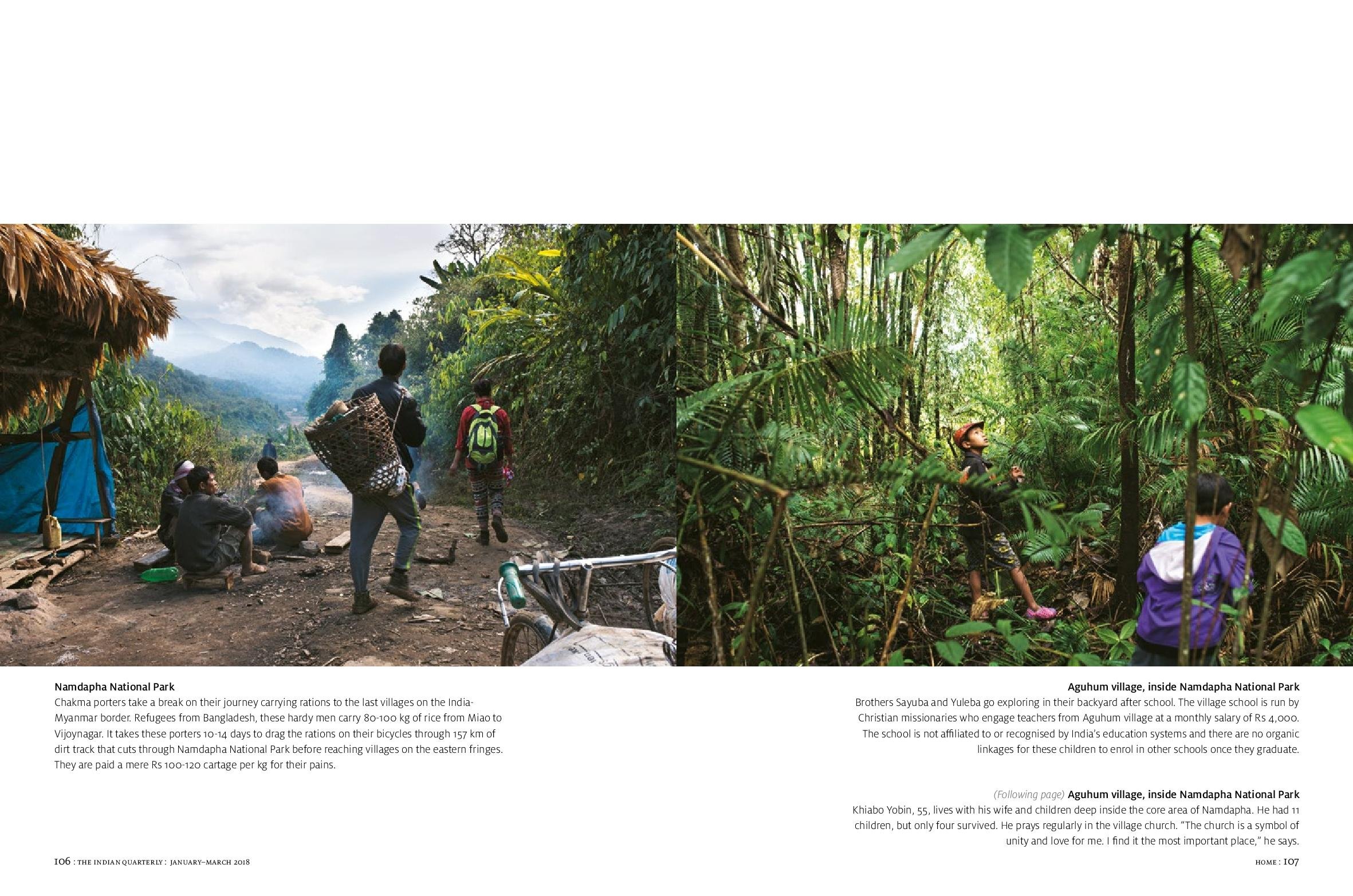

The Tibeto-Burman Lisu tribe has been living inside the dense contiguous forests of Namdapha spread over 20,000 sq. km from Arunachal Pradesh on the Indian side, into Myanmar. Their ancestors, a hunter-gatherer tribe from the Yunnan province in China— first reached Myanmar and then into India foraging for food — eventually settling in these Indian forests way before the India-Myanmar international border was demarcated in 1972. Distanced from the monetised economy bereft of most modern technological advancements, they made home in these forests.

Arunachal Pradesh is India’s remotest North-Eastern (NE) state sharing its border with Bhutan, China and Myanmar (East) with the highest tribal population in India and second richest biodiversity.

Until May 1961, when Assam Rifles (AR) made its first reconnaissance mission under Operation Srijitga to Dawodi (now Vijoynagar) led by Major Sumer Singh of 7th AR, the Indian government was largely unaware of the presence of Lisus in this region. At that time, the Indian government had no presence here and the India-Myanmar international border was yet to be demarcated, thus leaving the region completely ungoverned, porous and assumedly a no man’s land. In 1983, the Indian government converted declared 1985 sq. km. of their native land into Namdapha National Park & Tiger Reserve (NNP) on the India-Myanmar border of Arunachal Pradesh, India, without consulting or seeking the consent of the Lisus.

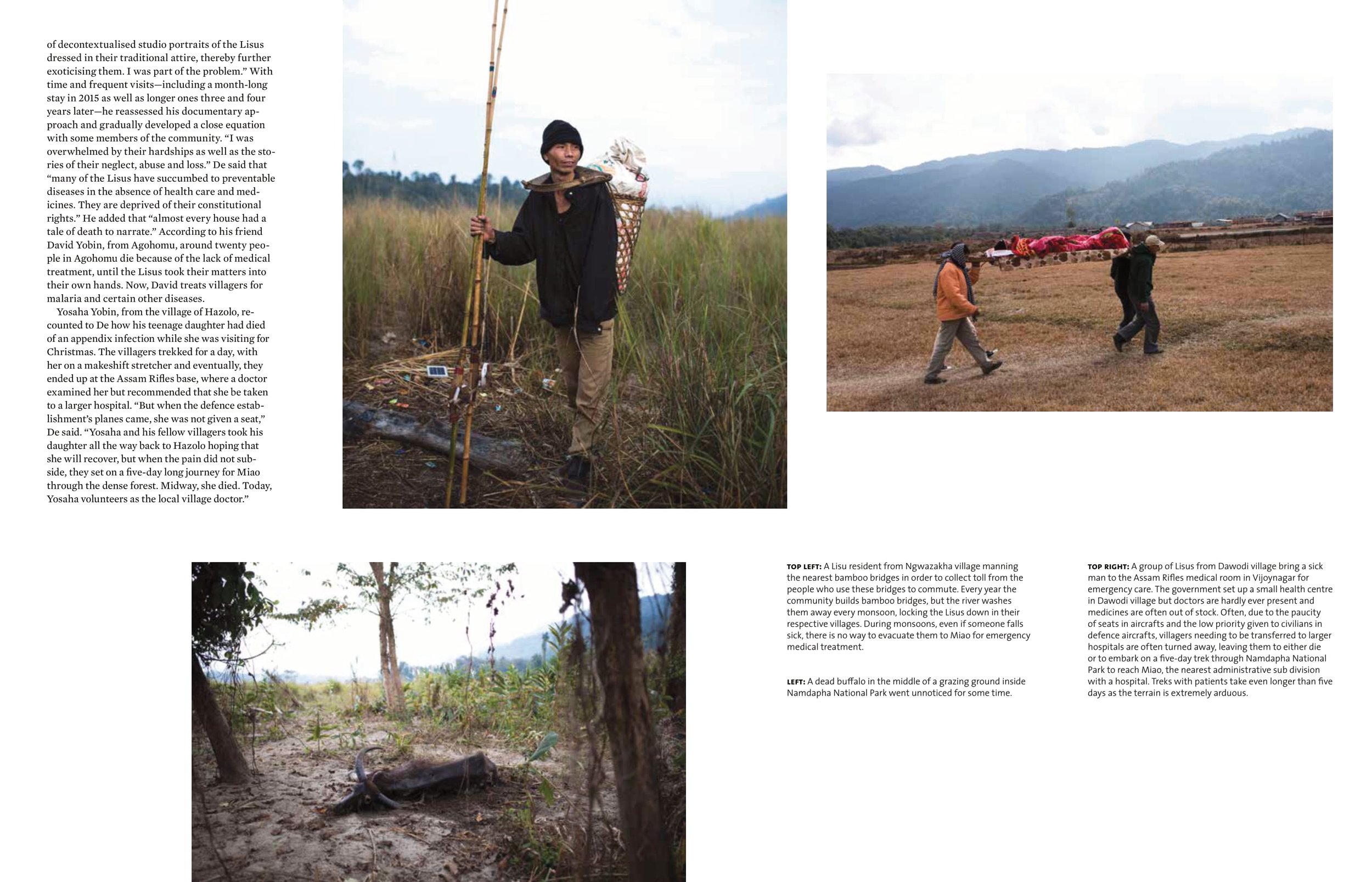

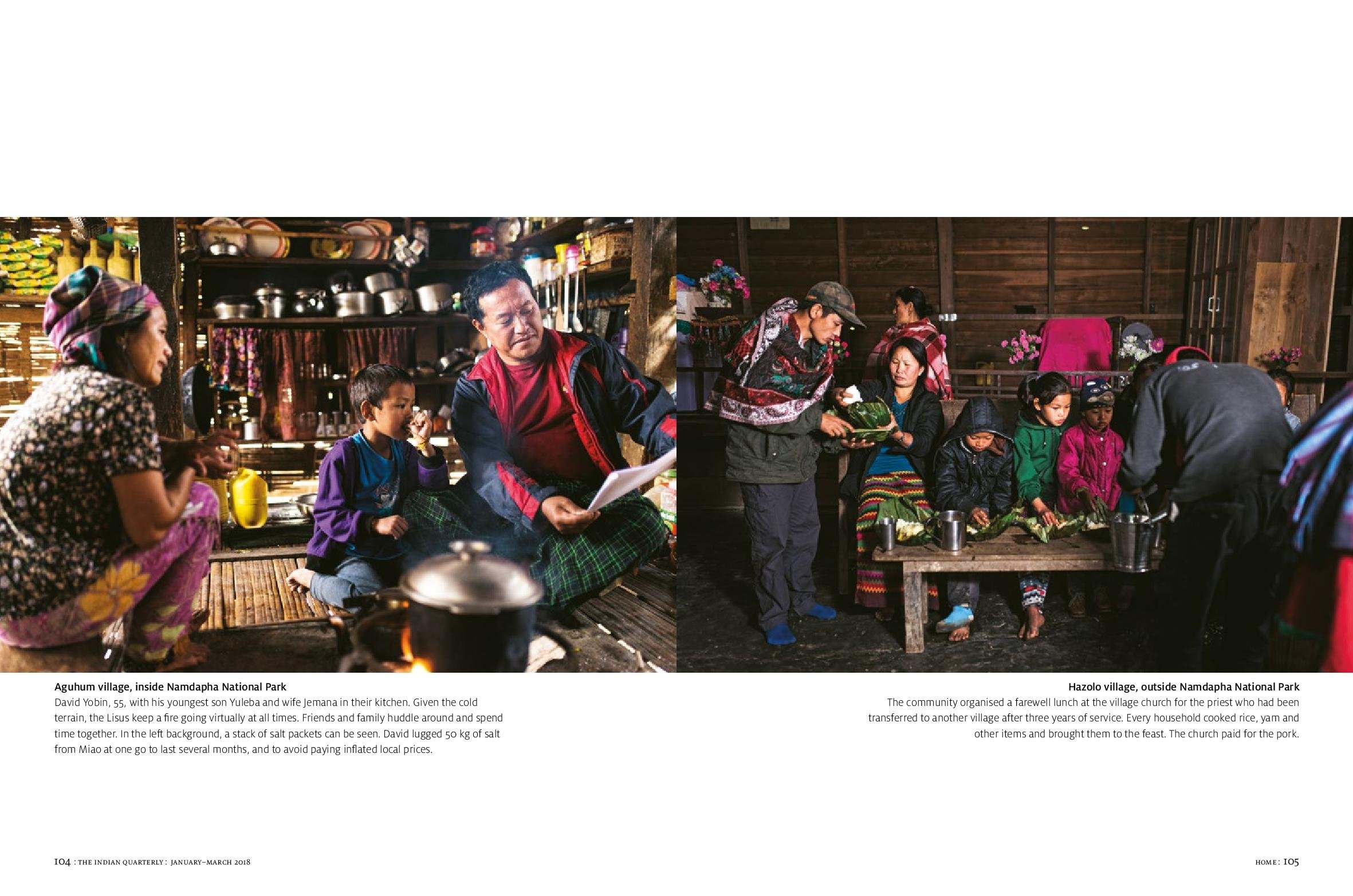

This singular act turned the domicile status of the Lisu villages (that now fell within the park area) as illegal, stripping them of their right to stake claim to their native land. Overnight, those Lisus were called ‘encroachers and poachers’ in their own land, and those who lived outside the park’s eastern periphery across villages like Gandhigram, Hazolo, Vijoynagar etc. were landlocked from both sides— park on the West and the international border on the East—pinning them down from all fronts. This is a bizarrely unique situation. It must be understood that NNP’s existence meant that no permanent roads could be constructed to connect these outlying villages to the nearest town and administrative subdivision Miao, as well as to the rest of India. This led to the genesis of a great degree of suffering for especially the Lisus but also the Nepali ex-servicemen settlers, though the latter enjoyed pensions and ration supplies. To illustrate the bizarreness of the situation, it is worth noting that the price of 1 kilogram salt generally worth Rs 25 (30Cent approx.), costs anything between Rs 80-150 (2 USD approx.) in this region, a three-five-fold increment. The same goes for the price of almost every other commodity in this region. Most cannot afford these exorbitant costs. Thus, they trek for three to six days through the dense forest braving inclement weather covering 120-157 km, all the way down to Miao, purchase essential daily provisions and carry them back on head load, usually trekking for anywhere between two-five days with a 30-50 kg weight. A noticeable impact of this can be witnessed in their food— as one moves further towards Dawodi, salt and oil content in their food reduces.

Close to eight decades of peaceful existence despite extreme deprivation, neglect and abuse by State and non-state forces in Independent India of the Lisu community went largely unnoticed by scholars, journalists and members of the intellectual community who perform a vital re-presentational and image-building/shaping role. When the Lisus were unconstitutionally deprived of their Scheduled Tribe (ST) status (from 1978 until 2018) with periods of intermittent and random reinstatements and cancellations over the years, local politicians advised them to claim themselves to be ‘Any Naga’ belonging to the Naga tribe so as to be able to enjoy benefits of existing tribal welfare policies. The Lisu leaders declined. They said, ‘We are not Nagas, and so cannot principally take benefits by claiming to be members of another tribe. We are Lisus’.

Though largely subsistence farmers, the Lisus do negotiate today’s monetised ecosystem with a modest degree of material and economic aspirations, especially the youth. Several of them have Facebook and email accounts. However, they also hold onto their ancient beliefs. Their creation tales and folklores, just like that of many other indigenous communities, bear similar motifs alluding to their entwined connections with nature and its myriad elements which can be witnessed in their daily life. Here life is expensive, and death is cheap. Their children die without treatment; those who survive, grow up without education. Abandoned and forgotten, they were alone then, and now. But abandoning the forest they call ‘home’ is inconceivable. They cohabit symbiotically with nature revelling in its mysteries, treat their sick, build each other’s home, pray, celebrate and mourn together.

Editorial Publications:

The Caravan, 2019:

China Life, 2019:

Vrij Netherland, 2019:

Indian Quarterly, 2018:

Select Exhibitions (Installation Images):

Artist Talks:

Press Reviews/Interviews:

Acknowledgments: Imagined Homeland is made possible through an Art Research Grant from the India Foundation for the Arts and a Photo Made Scholarship from the Lucie Foundation.

Note: Each mise-en-scène was created on location. No animals were hurt during the making of the series.